In part three of “Look Beneath The Surface,” our continuing series on culture, Dr. Mooney points out the ways people understand and adjust to the demands of time. It is another of the invisible dimensions of culture that can make or break communication across cultures, especially in the classroom.

Looking through our cultural glasses helps us to interpret what we see happening in the world. The assumptions, values, and beliefs built into those glasses tell us what makes a “good” mom, or how to respond to a stranger that approaches us, or what it means to show respect to someone else. Objectively speaking, there is nothing right or wrong with cultural glasses. Our perceptions of the world are based upon our culture, and the continuation of that cultural diversity depends upon those assumptions, values, and beliefs being explicitly and implicitly taught to future generations.

A large part of what we see through our cultural glasses are the actions of others. The invisible dimension of culture we learned from the society around us tells us what those actions mean. We interpret the actions of the woman toward her children at the park as being what a “good” mom or a “bad” mom does. A stranger crossing the dark street to walk toward us means something based on our cultural understanding.

We often don’t realize the actions of the parent or stranger mean different things depending upon the cultural glasses you wear. Miscommunications can occur when we look through our glasses to interpret another’s behavior. In essence, we view their behavior and say, “I know why you did that.”

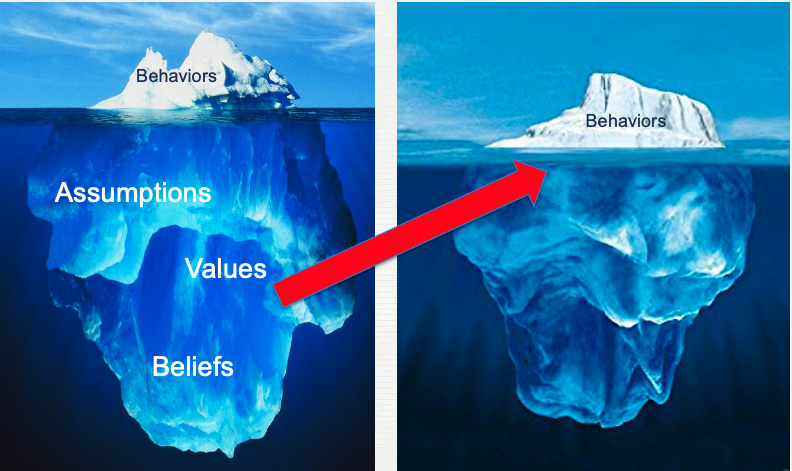

The truth is our interpretation of their motivations might be right. But it also might be wrong because we are applying the invisible dimension of our own culture to the visible dimension of another. A little bit like this…

We are assigning what drives OUR behavior (our assumptions, values, and beliefs) to someone else’s behavior. In considering cross-cultural interactions such as these, it is possible that what we thought was causing another’s behavior was not true at all. That’s because we can’t see what’s below the surface of their actions.

A common example of this miscommunication occurs in relation to our view of time.

Time

Cultures around the world perceive time differently. This is not to say that some cultures have more time in their day. We all have 24 hours. However, the way we interpret and relate to the aspect of time can vary widely.

Monochronic cultures view time as linear. They believe it can be spent or wasted because the feeling is that once you move past a point in time (12:30 pm on September 15, 2020) that time will never come again. The value of using the moment efficiently and productively is paramount. As a result of this deeply held value, schedules are very important, and interruptions to those schedules are a nuisance. Probably most significant is the idea that time is often valued more highly than people. People must adjust to the demands of time.

In contrast, Polychronic cultures perceive time as more fluid. It’s like a ribbon that ebbs and flows, and as result, people are likely to shift their attention between more than one thing in the same space of time. Because life cannot be fully predicted or planned, schedules should not be rigid. Interruptions are a natural part of life and should be seen as having value. People and relationships are more important that strict schedules.

In the classroom…

Stereotypically, Americans find themselves pretty far toward the Monochronic end of this continuum. Sometimes those living in large families or in small towns can identify more with the Polychronic view of life, but the overall framework of American society is built on a Monochronic view. You know this if you have ever shown up 15 minutes late for a doctor’s appointment and been made to reschedule to another day as a result.

English learners and their families from polychronic cultures may display behavior you don’t understand. You think you understand them as you look through your own cultural glasses, but your interpretation may be inaccurate. Imagine a parent showing up 30 minutes late for their Parent Teacher Conference. In a monochronically aligned school, this just doesn’t work. Each family gets 10-15 minutes with the teacher and the day is often fully booked before it begins. Squeezing in a parent who doesn’t come at their time may be impossible.

When this happens, a monochronic teacher may feel that the parent simply does not care about their child’s education, or they would have made it a priority to show up on time, or even a bit early. In reality, it may be that the polychronic parent did not realize how strict the schedules were. They also may have been on their way to the school when a neighbor or relative stopped to chat. To them, it is not that the teacher’s time is not important, but the relationship in front of them at the moment takes precedence. They care deeply about their child’s education, but they care about people more than getting somewhere “on time.”

What do you do?

Should the monochronic teacher be available for Parent Teacher Conferences 12 hours a day for 4 days so all the parents can eventually show up? No. That’s probably not the best solution.

However, schools serving families from traditionally polychronic cultures need to make the importance of schedules very clear. You cannot assume that families understand that they can only talk with the teacher if they arrive at X time. Be explicit and tell them more than once.

Another strategy is to find a solution that allows for more flexibility. Can the teacher be available for a block of time and allow parents to come and wait in line to talk? Can it be more of a reception type of environment where parents can mingle with each other and talk with the teacher, too? FERPA privacy laws would need to be considered, but this type of gathering might work for some topics or situations. Maybe the teacher could talk about overall issues with a group of parents and then meet individually for very short times to answer questions about their individual children.

Another issue affected by time is the school’s tardy policy. Is your school’s policy very rigid? Are students routinely late to school? How are they treated? An extremely monochronic position would cause a polychronic family to amass many tardy slips and the resulting consequences. Schools with many polychronic families should consider how they might work through this situation in a culturally sensitive way.

Are you looking through your cultural glasses and evaluating another’s behavior? Is your interpretation correct?

A conscientious teacher is willing to step back and contemplate whether cultural differences may be causing the behavior they don’t understand. Maybe that parent isn’t really “late.”

Next week…

Whether or not your students sense they have influence over what happens to them makes a huge difference. If not properly understood as one of the most invisible of dimensions, classroom interaction and communication can be mystifying. So, Dr. Mooney will take a look at the cultural dimension known as locus of control—a term unfamiliar to many.